The United Kingdom is getting serious about beaming solar power from space and thinks it could have a demonstrator in orbit by 2035.

Over 50 British technology organizations, including heavyweights such as aerospace manufacturer Airbus, Cambridge University and satellite maker SSTL, have joined the U.K. Space Energy Initiative, which launched last year in a quest to explore options for developing a space-based solar power plant.

The initiative believes that beaming electricity from space using the sun could help the U.K. meet its target of zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050 more cost-effectively than many existing technologies. The requirement to stop carbon emissions entirely by mid-century is part of global efforts to halt progressing climate change outlined at the United Nations’ COP 26 summit that took place in Glasgow in November 2021.

Speaking at the Toward a Space Enabled Net-Zero Earth conference held in London, the initiative’s chairman Martin Soltau said on April 27 that all technology required to develop a space-based solar power plant already exists; the challenge is the scope and size of such a project.

The initiative bases its plans on an extensive engineering study conducted by consultancy Frazer-Nash and commissioned by the U.K. government last year.

“The study concluded that this is technically viable and doesn’t require any breakthroughs in laws of physics, new materials, or component technology,” Soltau said.

The initiative has established a 12-year development plan that could see a demonstrator power plant, assembled by robots in orbit, beam gigawatts of power from space to Earth as early as 2035, Soltau said.

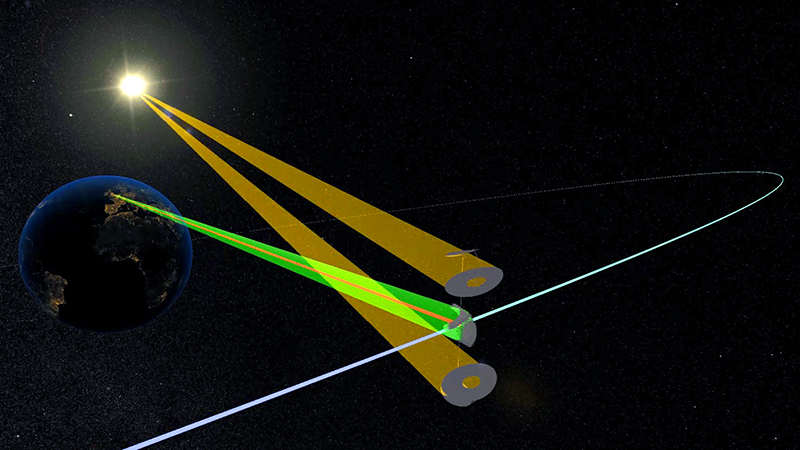

The initiative explores a modular concept called CASSIOPeiA (for Constant Aperture, Solid-State, Integrated, Orbital Phased Array), developed by the British engineering firm International Electric Company.

The modular nature of the orbiting power plant means it could be expanded after the demonstration phase. Even the demonstrator, however, would be giant, several miles across, and require 300 launches of a rocket the size of SpaceX Starship to deliver to orbit, said Soltau. It would orbit 22,000 miles above our planet (36,000 kilometers) with a constant view of the sun as well as of Earth.

“The principal functions of the satellite are collecting the solar energy via large, lightweight mirrors and concentrating optics onto photovoltaic cells, just like we do on Earth,” said Soltau. “They produce direct current electricity, that’s then converted into microwaves via solid state radio frequency power amplifiers and transmitted in a coherent microwave beam down to Earth.”

However, CASSIOPeiA would produce much more electricity than any terrestrial solar power plant of a similar size. Compared to a solar panel placed on Earth in the U.K., an identical solar panel in space would harvest over 13 times more energy, Soltau said.

In addition to that, a space-based solar power plant would not suffer from the intermittency problem, which plagues most renewable power generation on Earth. Sun doesn’t always shine on our planet and the wind doesn’t blow consistently. That means alternative electricity generators or battery storage have to be in place to prevent blackouts in unfavorable weather. Space, on the other hand, would provide consistent power output.

On top of that, technologies that would make the electricity system work based only on Earth-based renewable power do not yet exist.

“Energy storage technology doesn’t exist yet at the right price and scale,” said Soltau. “We need other technologies, because we don’t have a plan that adds up. Net- zero will be very difficult and space-based solar power can deliver an interesting option.”

The U.K. can cover over 40% of its current electricity needs by renewable power, but the demand for clean energy is set to triple over the next three decades, according to Soltau, as transport and heating infrastructure wean off fossil fuels.

To meet such a demand with offshore wind farms, the type of renewable technology currently making the greatest contribution to the U.K.’s energy mix, would require “a band of turbines 10 kilometers [6.2 miles] wide around the entire mainland coast of Britain,” according to Soltau.

The footprint of the ground-based infrastructure needed for the orbiting solar power plant would be much smaller.

To receive the energy from space, the system would need a giant Earth-based antenna, dubbed the rectenna. The rectenna receives the microwave radiation sent from space and converts it into direct current electricity, which is used for high-voltage transmission.

“The rectenna is like a big open net with small dipole antennas and would have to be 7 by 13 kilometers [4.3 to 8 miles] in size,” Soltau said. “That’s very large, but in the U.K. context, it would occupy only about 40% of the area of an equivalent solar farm.”

Speaking at the same conference, Andrew Ross Wilson, an aerospace engineering researcher at the University of Strathclyde in Scotland, agreed that a space-based solar power station is a realistic conception.

“The concept has been around since the 1960s,” he said, adding that among the challenges to make such a plant work is the question of what would happen with the giant structure after it reaches its end of life.

“We need to try and look at in-orbit recycling to actually go towards a more circular economy,” he said.

The public might be concerned about the potential radiation from this beamed electricity, but according to Ross, the risk is negligible.

“You’re more likely to receive more radiation from the phone in your pocket than you would if you were standing under one of the beams,” he said.

Soltau added that the plan has gathered support in the U.K. government as well as among energy experts.

“Space based solar power features in the National Space Strategy,” he said. “And there’s an initial £3 million [$3.7 million] for developing some of the underpinning technologies as part of the net-zero innovation portfolio.”