The most common cause of lazy eye is crossed eyes (strabismus) and it usually develops in early childhood. Parents may not initially notice the symptoms, so the problem is often discovered during a routine eye exam at school or by the pediatrician. The goal of treatment is to improve vision in the weaker eye which may be achieved by wearing glasses and patching the good eye to make the weaker eye work harder.

Anything that blurs a child’s vision or causes the eyes to cross or turn out can result in lazy eye. Common causes of the condition include: Muscle imbalance (strabismus amblyopia). The most common cause of lazy eye is an imbalance in the muscles that position the eyes.

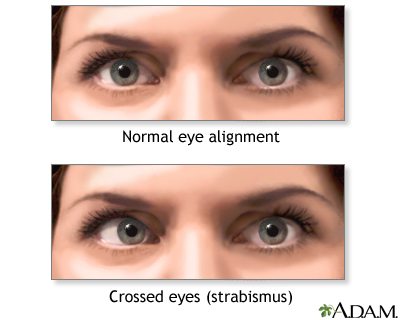

Strabismus (Crossed Eyes)

OVERVIEW

What is strabismus (crossed eyes)?

Strabismus (crossed eyes) is a condition in which the eyes do not line up with one another. In other words, one eye is turned in a direction that is different from the other eye.

Under normal conditions, the six muscles that control eye movement work together and point both eyes at the same direction. Patients with strabismus have problems with the control of eye movement and cannot keep normal ocular alignment (eye position).

Strabismus can be categorized by the direction of the turned or misaligned eye:

- Inward turning (esotropia)

- Outward turning (exotropia)

- Upward turning (hypertropia)

- Downward turning (hypotropia)

Other factors to consider that help determine the cause and treatment of strabismus:

- Did the problem come on suddenly or over time?

- Was it present in the first 6 months of life, or did it occur later on?

- Does it always affect the same eye, or does it switch between eyes?

- Is the degree of turning small, moderate, or large?

- Is it always present, or only part of the time?

- Is there a family history of strabismus?

What are the types of strabismus?

There are several forms of strabismus. The two most common are:

- Accommodative esotropia: This often occurs in cases of uncorrected farsightedness and a genetic predisposition (family history) for the eyes to turn in. Because the ability to focus is linked to where the eyes are pointing, the extra focusing effort needed to keep distant objects in clear focus may cause the eyes to turn inward. Symptoms include double vision, closing or covering one eye when looking at something near, and tilting or turning the head. This type of strabismus typically starts in the first few years of life. This condition is usually treated with glasses, but may also require eye patching and/or surgery on the muscles of one or both eyes.

- Intermittent exotropia: In this type of strabismus, one eye will fixate (concentrate) on a target while the other eye is pointing outward. Symptoms may include double vision, headaches, difficulty reading, eyestrain, and closing one eye when viewing far away objects or when in bright light. Patients may have no symptoms while the ocular deviation (difference) may be noticed by others. Intermittent exotropia can happen at any age. Treatment may involve glasses, patching, eye exercises and/or surgery on the muscles of one or both eyes.

Another type of strabismus is called infantile esotropia. This condition is marked by a large amount of inward turning of both eyes in infants that typically starts before six months of age. There is usually no significant amount of farsightedness present and glasses do not correct the crossing. Inward turning may start on an irregular basis, but soon becomes constant in nature. It is present when the child is looking far away and up close. The treatment for this type of strabismus is surgery on the muscles of one or both eyes to correct the alignment.

Adults can also experience strabismus. Most commonly, ocular misalignment in adults is due to stroke, but it can also occur from physical trauma or from a childhood strabismus that was not previously treated or has recurred or progressed. Strabismus in adults can be treated in a variety of ways, including observation, patching, prism glasses and/or strabismus surgery.

How common is strabismus?

It is estimated that four percent of the U.S. population, or about 13 million people, have strabismus.

SYMPTOMS AND CAUSES

What causes strabismus?

Most strabismus results from an abnormality of the neuromuscular control of eye movement. Our understanding of these control centers in the brain is still evolving. Less commonly, there is a problem with the actual eye muscle. Strabismus is often inherited, with about 30 percent of children with strabismus having a family member with a similar problem.

Other conditions associated with strabismus include:

- Uncorrected refractive errors

- Poor vision in one eye

- Cerebral palsy

- Down syndrome (20-60% of these patients are affected)

- Hydrocephalus (a congenital disease that results in a buildup of fluid in the brain)

- Brain tumors

- Stroke (the leading cause of strabismus in adults)

- Head injuries, which can damage the area of the brain responsible for control of eye movement, the nerves that control eye movement, and the eye muscles

- Neurological (nervous system) problems

- Graves’ disease (overproduction of thyroid hormone)

When do the symptoms of strabismus appear?

By the age of 3 to 4 months, an infant’s eyes should be able to focus on small objects and the eyes should be straight and well-aligned. A 6-month-old infant should be able to focus on objects both near and far.

Strabismus usually appears in infants and young children, and most often by the time a child is 3 years old. However, older children and even adults can develop strabismus. The sudden appearance of strabismus, especially with double vision, in an older child or adult could indicate a more serious neurologic disorder. If this happens, call your doctor immediately.

A condition called pseudostrabismus (false strabismus) can make it appear that a baby has crossed eyes when in fact the eyes are aiming in the same direction. Pseudostrabismus can be caused by extra skin covering the inner corners of the eyes and/or a flat nasal bridge. As the baby’s face develops and grows, the eyes will no longer appear crossed.

DIAGNOSIS AND TESTS

How is strabismus diagnosed?

Anyone older than four months of age who appears to have strabismus should have a complete eye examination by a pediatric ophthalmologist, with extra time spent examining how the eyes focus and move. The exam may include the following:

- Patient history (to determine the symptoms the patient is having, family history, general health problems, medications being used and any other possible causes of symptoms)

- Visual acuity (reading letters from an eye chart, or examining young children’s visual behavior)

- Refraction (checking the eyes with a series of corrective lenses to measure how they focus light). Children do not have to be old enough to give verbal feedback when checking for glasses.

- Alignment and focus tests

- Examination after dilation (widening) of the pupils to determine the health of internal eye structures

MANAGEMENT AND TREATMENT

How is strabismus treated?

Treatment options include the following:

- Eyeglasses or contact lenses: Used in patients with uncorrected refractive errors. With corrective lenses, the eyes will need less focusing effort and may remain straight.

- Prism lenses: Special lenses that can bend light entering the eye and help reduce the amount of turning the eye must do to look at objects.

- Orthoptics (eye exercises): May work on some types of strabismus, especially convergence insufficiency (a form of exotropia).

- Medications: Eye drops or ointments. Also, injections of botulinum toxin type A (such as Botox) can weaken an overactive eye muscle. These treatments may be used with, or in place of, surgery, depending on the patient’s situation.

- Patching: To treat amblyopia (lazy eye), if the patient has it at the same time as strabismus. The improvement of vision may also improve control of eye misalignment.

- Eye muscle surgery: Surgery changes the length or position of eye muscles so that the eyes are aligned correctly. This is performed under general anesthesia with dissolvable stitches. Sometimes adults are offered adjustable strabismus surgery, where the eye muscle positions are adjusted after surgery.

What can happen if strabismus is not treated?

Some believe that children will outgrow strabismus or that it will get better on its own. In truth, it can get worse if it is not treated.

If the eyes are not properly aligned, the following may result:

- Lazy eye (amblyopia) or permanent poor vision in the turned eye. When the eyes are looking in different directions, the brain receives two images. To avoid double vision, the brain may ignore the image from the turned eye, resulting in poor vision development in that eye.

- Blurry vision, which can affect performance in school and at work, and enjoyment of hobbies and leisure activities

- Eye strain

- Fatigue

- Headaches

- Double vision

- Poor 3-dimensional (3-D) vision

- Low self-esteem (from embarrassment about one’s appearance)

It is also possible that by not diagnosing strabismus, a serious problem (such as a brain tumor that is causing the condition) may be overlooked.

OUTLOOK / PROGNOSIS

What can be expected after treatment for strabismus?

The patient will need to see the doctor for follow-up to see if the patient has responded to treatments, and to make adjustments, if necessary.

In the case of children with strabismus, if the condition is caught in time and properly treated, it can result in excellent vision and depth perception and can protect against loss of vision.